Theory & Practice, Michelle de Kretser [Catapult]

Caravaggio 2025, [Gallerie Nazionali Barberini Corsini]

There is a perfect chapter halfway through Michelle de Kretser’s 2012 Questions of Travel. Laura has taken an office job after years of freelance. In seven pages, de Kretser recounts a banal, fussy corporate day, mostly by describing the emails that arrive in Laura’s inbox:

It was like being dropped into a country where she didn’t understand the language: the disorientation, the constant switching of focus, the way the trivial and the momentous presented on the same plane.

de Kretser’s new novel, Theory & Practice, is a beautifully slim 178 pages. I read it in a single day across two cafes in Rome and then turned around and read it again on the airplane ride home. It starts as a historical novel, stops, changing its mind to tell the story of a novelist in the years before she becomes one.

Cindy has moved from Sydney to Melbourne to do her MA on Virginia Woolf. She falls into friendships and a romance with Kit where she is the other woman. “‘We have a deconstructed relationship,’ he said. The calculated way he said ‘deconstructed’ amused me — he was producing the price of admission to the palace of cool.” Kit’s girlfriend occupies as much space in her mind as he does. Olivia with her marble face and beaten gold hair.

The real relationship is between Cindy and the inspiring and racist subject of her thesis: Virginia Woolf. I didn’t realize I’d been longing to read more on the problems of Woolf since I read a collection of unpublished sketches a few years ago and wasn’t sure I wanted to tell anyone because they troubled me so much. Doris Lessing wrote the introduction: “With Woolf we are up against a knot, a tangle of unlikeable prejudices, some of her time, some personal …”

de Kretser is delicious on the tortured poses of academia. Who is allowed to tell truth and who is asked to set it aside in favor of a “critical read.” Who is allowed to stay on the altar once we’ve discovered their clay feet. “Ten minutes with her,” says one character of Woolf, “and I’d be calling for a gun […] But she helped build my brain, you know?”

The hotbox of campus life and the people who surround an academic stopover are exactly drawn. I like

’s definition of a campus novel:What I love about campus fiction is that is provides a world in miniature whose rules and laws and rigors can be stand-ins for the rules, laws, and rigors of the broader world. The other thing I love about campus fiction is that it often provides a crucible for conflict and drama that might not occur elsewhere. Because a campus often draws people into relation who might not otherwise have been in such relations.

de Kretser threads the whole novel together at the end in a bright loop. The first, abandoned novel returns in the final scenes. As with all love affairs, both Woolf and Kit fade, even as they never lose their importance. “Many years had to pass before I’d realise that life isn’t about wishes coming true but about the slow revelation of what we really wished.”

We leave the past, but it always returns in bright flashes.

—

At the Palazzo Barberini in Rome there is a “blockbuster” Caravaggio exhibit up until July. It contains two previously undisplayed paintings, several works that reside in the U.S. and a piece loaned by H.M. Charles III.1 Rome of course is full of other Caravaggios—three at the Galleria Doria Pamphilj and the Contarelli chapel at the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi. (If you have to pick one, do the church and enjoy St. Matthew surrounded by nudes.)

The gallery walls at Barberini are dark, and the paintings lit so harshly that getting close doesn’t reward you with anything but glare. Fellow viewers occasionally come into focus thanks to bright pockets of cell phone screens held close to hear the audio tour.

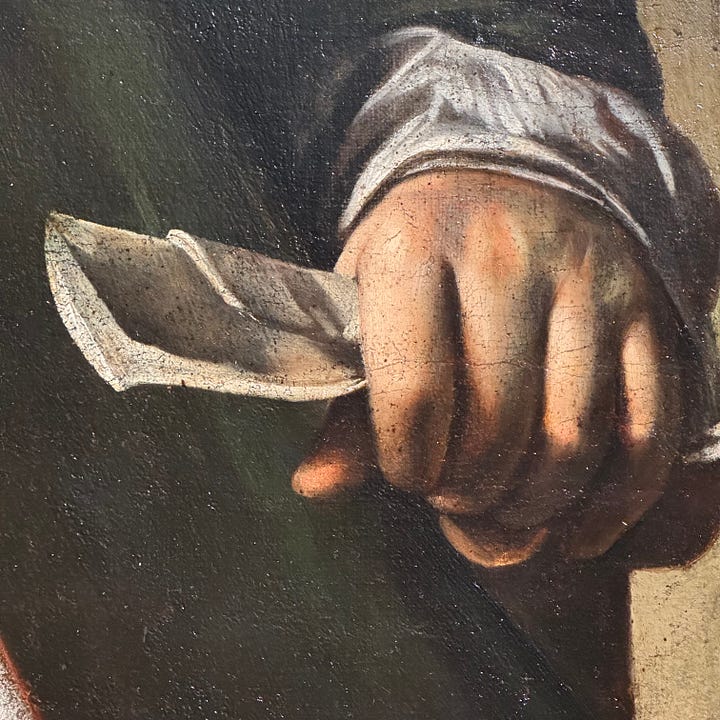

I think of Caravaggio as a painter of faces, but I noticed the hands and the limbs. In Boy Peeling Fruit (1595, The Royal Collection) the blush of exertion on the knuckles mirrors the peaches underneath.

You don’t see much of the knife, just the blade emerging out from the curl of lemon.

In the portrait of Maffeo Barberini (1598, private collection), the knuckles of his left hand are gouged deep red from the strength of his grip on the paper.

In Saint John the Baptist in the Wilderness (1602, Nelson-Adkins Museum of Art) Caravaggio defines the calf into the ankle with a shadow that leads into the dirt around his big toenail. (In the catalogue, Francesca Cappelletti notes Caravaggio’s dingy realism: “beautiful girls with somewhat marked features, and dirty feet and blackened nails just about everywhere.”) Saint John’s chest is sort of a confused muddle, and yet you want it to be confused because it lets the limbs emerge.

You can stand just the right of the doorway between two of the galleries and turn your head to look first at Judith Beheading Holofernes (1599, Palazzo Barbarini) and then David with the Head of Goliath (1606, Galleria Borghese). Judith, in three-quarter profile with a look of concern and disgust even as her arms are strong in the cutting. David, front facing but half in shadow, his clavicles blushed with shame or exertion.

“Another thing Lenny told me,” de Kretser writes, “was that for a long time the artist he’d admired most was Caravaggio.”

“I can’t look at those paintings these days. Everyone in them looks ill.”

The provenance note in the catalogue on Boy Peeling Fruit is unparalleled: “Probably acquired by Charles II, but first recorded in the 1688 inventory of James II’s works […] ‘By Michel Angelo — A work, representing a boy in a shirt, peeling fruit.’”

DELICIOUS