Thiebaud + Laing

You should do something that you know about, that you're infatuated with

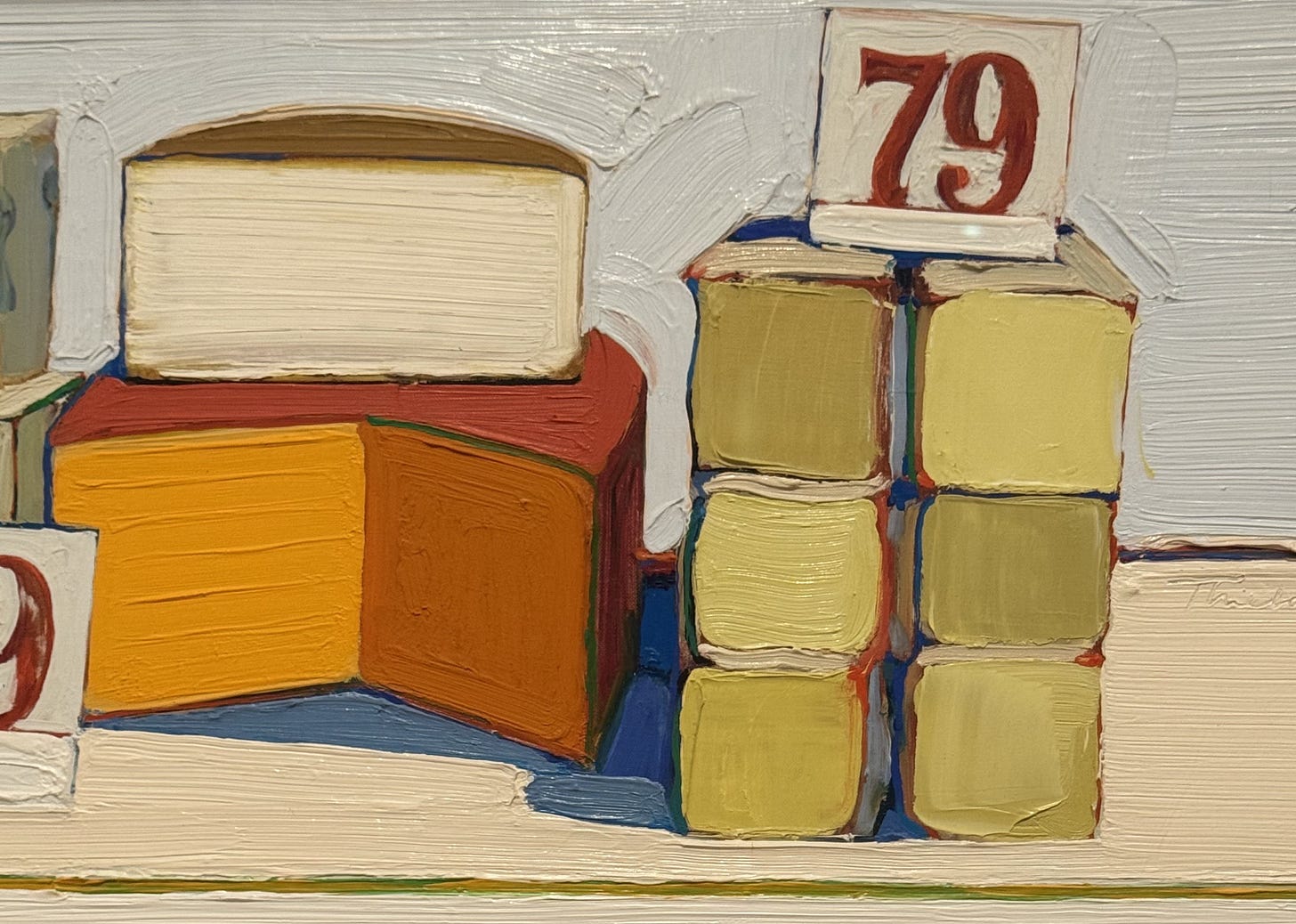

American Still Life, Wayne Thiebaud [Courtauld]

The Silver Book, Olivia Laing [Hamish Hamilton]

I’m increasingly interested in a museum that I think of as jewel-box sized. Big enough that you and a friend can lose each other exploring it, but small enough to take in the whole collection in about an hour.

The Courtauld in London is a jewel box museum. Right now, on the top floor is “American Still Life,” the first UK museum exhibition of Wayne Thiebaud (White Cube held an exhibition that included his landscapes in 2017). Two rooms of cakes and pies and hot dogs lined up for inspection. Edible goods in calm repose against thickly described backgrounds in shades of winter butter.

Thiebaud trained as a commercial painter1, and the wall text notes how he lovingly recreates hand-drawn price signage for sausages, cheese, peppermints. American Cheese, or is it butter, in “Delicatessen Counter” (1942), is almost pulsating thanks to edges described in green, red, and a blue the same shade as the Courtauld’s spiral staircase.

Ian Parker profiled Thiebaud for the New Yorker in 2014. (Thiebaud painted covers frequently for the magazine.) They go to a cake shop on East 87th street, and Thiebaud shows up, “wearing a blue windbreaker from which he had not yet removed day-old proof-of-payment stickers from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney--Thiebaud’s work is in both collections--and he looked like a high-school athletic coach a week or two into retirement.” A fall look worth recreating.

Thiebaud is from Arizona and California, and there’s something of the West’s flat, unceasingly light in how he executes a still life. Taking the advice of his mentors, he started painting what he knew, rather than the Ab Ex of the time. “I was interested in the Americanism of gumball machines.” (There’s a nice aside about his “exasperated” dealer when Thiebaud moved on to landscapes: “Jesus Christ, I’ve just got people used to those damn pies.”)

Little tips of hot dogs sticking out of the edge of a bun. Cake slices cut to diner-like sameness. Thiebaud’s still lives resonate not because of repetition but because of the tiny imprecise detail. He told Parker he painted the meringues and pumpkin pies from memory. There’s a type of error, of distortion that becomes beautiful because it comes from human hands.

—

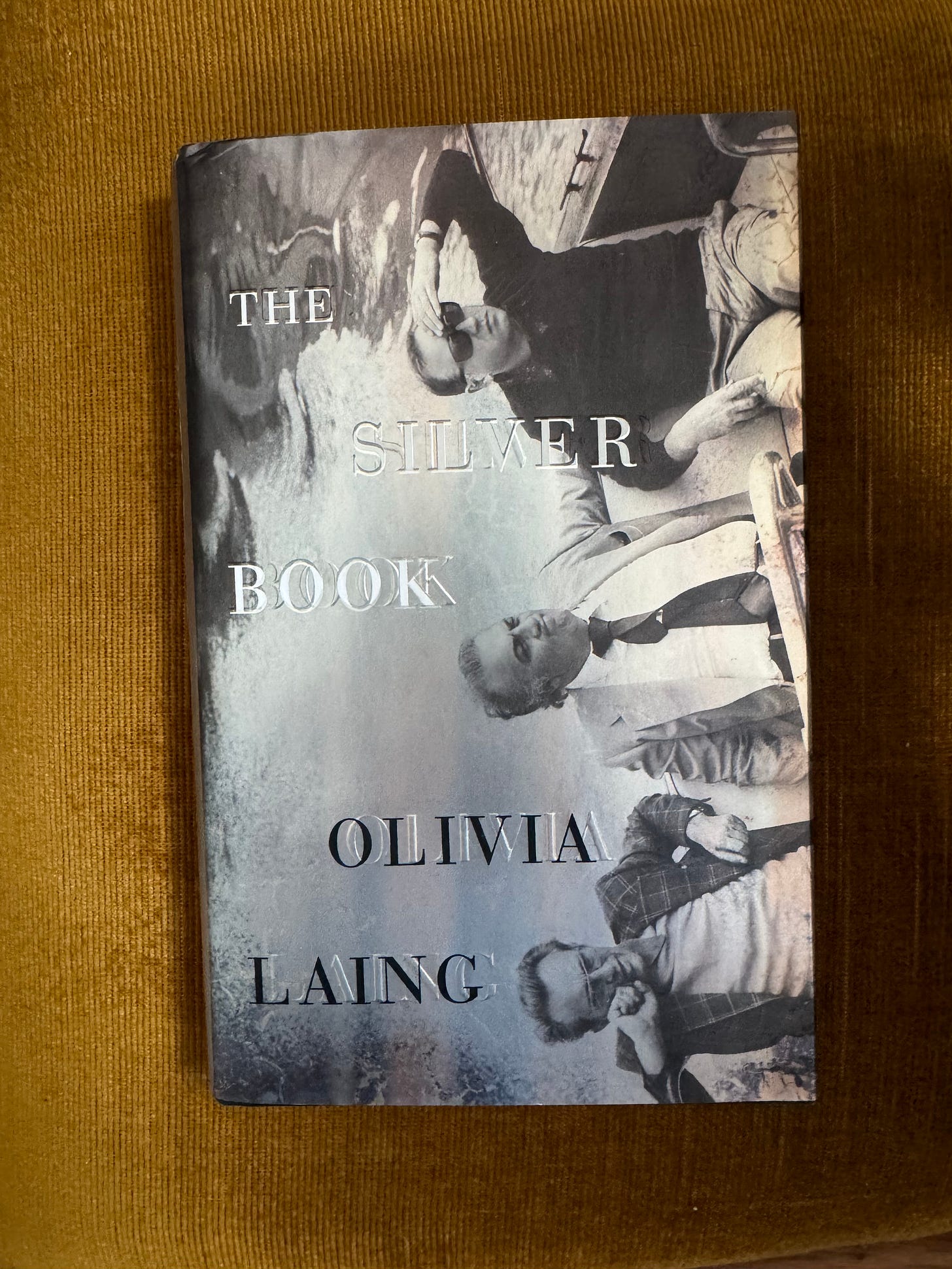

Olivia Laing’s new novel, The Silver Book, comes wrapped like a confection. The cover tarnished silver, the end papers preserved-cherry colored velvet drapes. It’s a spare novel. And even though it is studded with death, it is fiercely, utterly focused on the act of creation.

Most of the characters are real—the maestros of 60s and 70s Italian cinema, and Donald Sutherland in a goofy, sincere cameo.2 As Laing puts it in an end note “some of the events described did happen, though no doubt not quite like this.” The novel unfolds in 1975 across the sets of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salo and Federico Fellini’s Casanova. We traverse this world through Nicolas, the young English lover of costume designer Danilo Donati.

Laing pulls off this lovely trick of getting you very close to the hardest of emotions and then, just like in real life, turning back to the demands of work. Nicolas takes on work on the sets of both films, constructing Fellini’s false Venice in on a cinema lot in Rome and assisting with the carefully constructed fascist uniforms of Pasolini’s Salo:

A few days later, he watches Hélène Surgère zip herself up and come sweeping back into the room. White satin, huge skirt, sleeves like water wings, embellished with black rosettes, vaguely arachnoid, vaguely floral. Evil flowers, he calls it to himself: a dress that epitomizes the fascist stance. Pure surface, absolute dominance, the absence of a heart. Hélène leans into the mirror, scoops back her hair, tries out a laugh. I hate it, she says. It makes my blood run cold, and Pasolini smiles.

As Nicolas discovers this world, so do we. The two films Nicolas works are notoriously difficult films. Casanova written off as a flawed masterpiece: “we have taken one ride too many on [Fellini’s] merry-go-round” (Sight and Sound upon its release in 1977). And Salo: “awful in 1975, and is still awful now” (BBC upon a 2000 reissue), “a perfect example of the kind of material that, theoretically, anyway, can be acceptable on paper but becomes so repugnant when visualized on the screen that it further dehumanizes the human spirit, which is supposed to be the artist’s concern” (the NYT upon its premier at the New York Film Festival).

Laing lets all the men in the novel be human. Cook meals. Pick up lovers. Work through their films as intellectual exercises we may or may not like the outcomes of. Cinema, at least in 1975, is “a repository of dreams, built by hand by people like Donati.”

Her affection for her characters is clear. The novel has the highest respect for handmade illusion. Her addition of fiction to the very real death of Pasolini feels like a wonderful double of his use of de Sade to explore Italian fascism. Realism layered with fiction: a portrait more real than the truth. Exacting slices of cake, outlined in lurid, unreal green and blue.

He also worked for Disney and served in the Air Force in the “First Motion Picture Unit” during World War II.

Donald Sutherland and his glorious obit-making sex scene had been the lead in 1973’s Don’t Look Now.